The Comeback Model

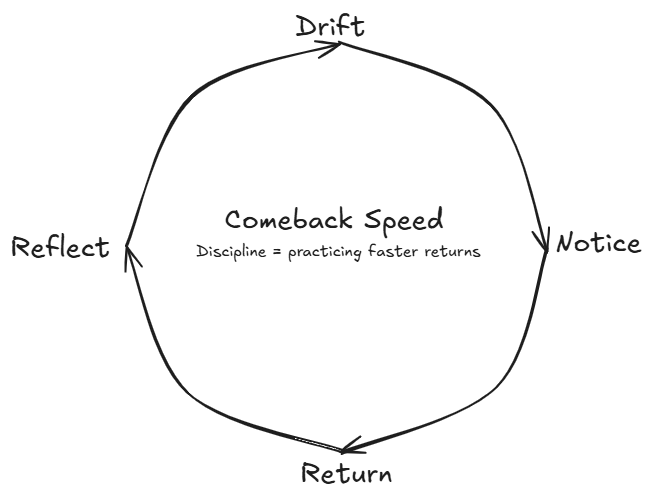

The Comeback Model is the behavioral engine of Adaptable Discipline. While the four Pillars define the philosophical foundation (Mindset, Purpose, Tools, Metrics), this model shows how those principles interact in practice: a loop of disruption, awareness, return, and reflection that turns setbacks into data instead of failure.

Think of Adaptable Discipline as:

- Framework: The entire system.

- Pillars: The high-level philosophy.

- Models: Dynamic mechanisms (like the Comeback Model) that bring it to life.

- Constructs: Components inside a model that describe its moving parts.

Role in Adaptable Discipline

The Comeback Model reframes success not as perfect consistency but as the ability to return quickly and intentionally after disruption. Every person drifts—focus falters, schedules collapse, life interrupts. Comeback speed determines whether discipline is sustainable.

Traditional models reward streaks and punish breaks, creating cycles of guilt and avoidance. The Comeback Model rejects this binary. Instead, it measures your response to setbacks, treating each return as a deliberate skill. This model shifts the question from “How do I never fall?” to “How do I recover faster, with clarity, and without shame?”

Core Ideas

Drift Is Inevitable

Behavioral science shows that lapses are a natural part of habit formation. Neural circuits that support habits rely on repetition, but even highly automated patterns are disrupted by stress, novelty, and competing demands. Accepting drift removes the emotional friction of shame, clearing the path for a faster reset.

Comeback Speed as a Metric

Comeback speed measures the time gap between deviation and re-entry.

- Micro-drifts: Seconds-to-hours gaps (e.g., scrolling too long before resuming work).

- Macro-drifts: Days-to-weeks gaps (e.g., stopping a fitness routine).

Tracking comeback speed provides a dynamic metric: over time, your gaps shorten, and your ability to re-engage strengthens.

The Feedback Loop

The model is cyclical:

- Disruption → A deviation triggered by environment, emotion, or context.

- Recognition → Awareness of drift; the brain shifts from automatic mode to reflective control.

- Return → A deliberate action to re-align with chosen priorities.

- Integration → Post-drift reflection solidifies learning, reducing shame and increasing resilience.

This loop converts setbacks into feedback, not evidence of failure.

Constructs

Awareness

A core construct of comeback speed is situational awareness. Neuroimaging research shows that activation of the prefrontal cortex is crucial for interrupting automatic patterns. Practical implication: strengthening self-awareness accelerates recognition of drift.

Grace

Shame lengthens comeback time. The Comeback Model emphasizes grace as a psychological tool—compassionate self-talk reduces emotional resistance and encourages earlier re-engagement.

Keystone Anchors

Anchors are minimal habits or rituals that provide stability even in chaos. They act as low-friction entry points when motivation is low, helping you restart with less cognitive load. Examples include a 1-minute meditation, writing a single sentence, or setting a single priority for the day.

Elastic Discipline

Comeback speed depends on flexibility. Systems designed for elasticity—adjustable intensity, alternative environments, fallback rituals—make returning easier. Elasticity acknowledges that context changes, and so should your response.

Optional Insights

These entries go deeper into the science and context behind the Comeback Model.

They’re not required to understand the model’s mechanics but provide:

- Scientific depth: Neuroscience and psychology that explain why the loop works.

- Behavioral framing: Insights into emotional and cultural patterns that affect comeback speed.

- Advanced context: Bigger-picture implications for resilience and sustainable discipline.

Neurobiology of Return

Definition:

The Neurobiology of Return explains how the brain reinforces comeback behavior at a chemical and structural level. Returning to a task reactivates reward pathways, creating a feedback loop that strengthens resilience.

Mechanism:

The basal ganglia and prefrontal cortex are central to habit formation and decision-making. During drift, dopamine signaling often dips, making effort feel heavier. When you choose to return, dopamine release increases, rewarding the act of re-entry rather than the completion of a streak. Over time, this conditions the brain to value the comeback itself, lowering the friction of future restarts.

Implication:

Prioritizing comeback speed aligns with how your brain naturally learns: each restart rewires reward prediction and strengthens neural pathways for resilience. This approach replaces streak-based systems that punish breaks with a model that encourages flexible engagement.

Connections:

- Mindset: Supports the philosophy that "every comeback counts," reducing perfectionism.

- Metrics: Justifies measuring comeback speed over streak length.

- Tools: Reinforces the value of low-friction actions that trigger dopamine release quickly.

Emotional Decay Curve

Definition:

The Emotional Decay Curve describes how the psychological cost of returning to a task or habit increases disproportionately the longer you stay away. Over time, avoidance reinforces itself, creating a compounding emotional barrier to restarting.

Mechanism:

Behavioral research shows that avoidance cycles strengthen through negative reinforcement: each time you delay a return, the immediate relief from not confronting discomfort becomes rewarding, while shame or anxiety grows in the background. Cognitive load also rises as the unfinished task accumulates emotional weight, making it feel harder than it is. This results in a nonlinear curve: short gaps are easy to close; longer gaps create steep emotional resistance.

Implication:

Comeback speed isn’t about perfection—it’s about shrinking this curve. Returning quickly prevents emotional inertia from taking hold, reducing shame and cognitive load, and building confidence in your ability to restart. Tracking comeback speed over time helps normalize small gaps and focus on momentum instead of streaks.

Connections:

- Tools: Supports like fallback routines and environment design help interrupt avoidance cycles.

- Mindset: Grace and self-compassion reduce the emotional weight of lapses.

- Metrics: Measuring comeback speed offers a healthier alternative to streak tracking, encouraging frequent re-entry without guilt.

Cultural Implications

Definition:

Cultural Implications examines how perfectionism, hustle culture, and productivity narratives shape discipline norms—and why they make streak-based systems unsustainable for many people.

Mechanism:

Cultural messaging often glorifies grit, “never missing a day,” and extreme consistency, which fuels shame when people drift. This messaging disproportionately harms neurodivergent individuals, caregivers, and high-pressure professionals, who face unpredictable demands. Research on social comparison and burnout shows these pressures create a feedback loop: unrealistic standards lead to burnout, which increases drift, which reinforces feelings of inadequacy.

Implication:

By shifting focus from streaks to comeback speed, the model provides a psychologically safe and culturally counteractive approach to discipline. It validates non-linear growth, makes space for life’s unpredictability, and reframes lapses as data instead of moral failure.

Connections: